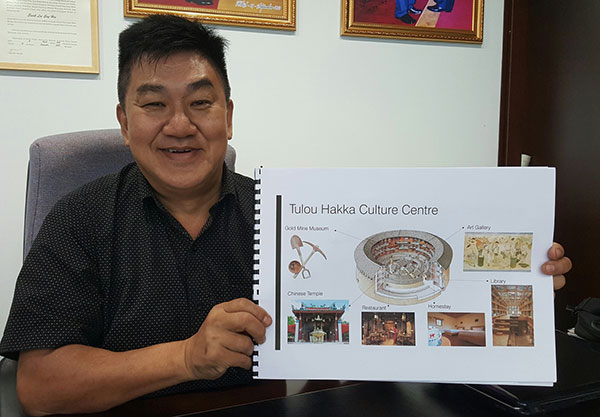

Lee shows the plan of the Tulou Hakka Culture Centre.

ORIGINALLY, they functioned as village units, offering safety, shelter and a sense of community.

Called tulou, they once served as home, fortress and even marketplace for China’s Hakka people, a Han sub-group that wandered into southern China about 2,000 years ago.

During that era, the bandits would roam the countryside, posing security threats to the Hakkas. The Fujian communal earthen buildings, which housed large families and sometimes multiple groups, were provided the clan protection from marauders.

Today, there are thousands of tulou across southern China. The odd-looking structures can stand as low as one storey, and serve as homes to one extended family.

Meaning ‘round structure’ in English, this great work of architectural art is found nowhere else in the world. But, no, we may not have to go as far as to China to see this kind of large civilian residence if the plan to build one in Bau becomes reality. The blueprint for the proposed Bau Hakka Cultural Village, which envisions the tulou in China, has been drawn up.

Ricky Lee, a coordinator of the proposed project, said professionals from Kota Kinabalu and a prominent consultant firm in Kuching have been engaged to prepare the Master Plan.

He said everything is ready now — just waiting for funding and implementation.

Lee said Tasik Biru assemblyman Datuk Peter Nansian is the man behind the proposed Hakka Cultural Village.

“Nansian has a vision for Bau and he sees tourism as an impetus for economic activities to boost the incomes of the locals. The proposed Hakka Cultural Village is a component of the Western Sarawak Tourism Master Plan he has personally worked on,” he added.

The plan, encompassing areas from Kuching to Samatan, is aimed specially at developing tourism products in Bau.

Lee also disclosed the proposed Tulou Hakka Culture Centre in Bau would comprise a goldmine museum, a Chinese temple, a restaurant, a homestay and an art gallery. The site has been identified near Tasik Biru within the Taiton area.

Nansian (centre) and Lee (4th right) with the Hakka delegates from Bau

and Kuching during a visit to China in 2013.

Tulou study trio

Lee said he and Nansian, who is Assistant Minister of Industrial Estate Development, even visited China with Hakka delegates from Kuching and Bau to study the structural features of the tulou.

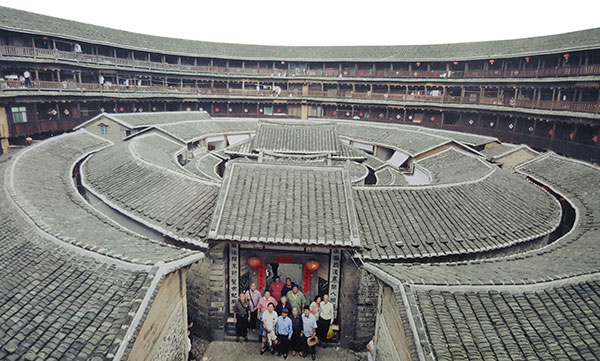

Tulou are round buildings having tall well-fortified mud walls, capped by tiled roofs with wide over-hanging eaves. They usually consist of external rammed earth walls and internal wooden framework, built on the base of stones, and the raw soil is kneaded, pounded and rammed again and again with lime, and fortified with fine sand, bamboo strips and wood. Normally, the roof is covered with long-lasting burnt tiles.

These Fujian earthen homes were built for a whole clan to live together, and could be as high as four or five storeys, providing enough space for three or four generations to live in the same building.

Lee said the tulou in Bau may not be built of earth or clay because it might be impractical in this modern era, adding that China’s tulou were built hundreds of years ago, and one could only wonder how they got the earth or clay in those days.

However, he pointed out that the Hakka Culture Centre in Bau would maintain the main features — shape and interior concept — of the original tulou.

“Like those buildings in China, bricks will be used to construct the round buildings. They cannot be called tulou if they’re not round because tulou means round building. Some of the rooms will be converted for homestay while there will be another building inside to house the gold mine museum, the restaurant and the art gallery,” he explained.

Lee commended Nansian for coming up with such a great idea, saying not even a Chinese leader had ever thought of having this sort of centre for the community.

He also concurred with the Tasik Biru assemblyman that Bau is the most suitable place to build a tulou because of its history. The Hakka Cultural Village itself will commemorate the historic arrival of the Hakkas to mine for gold in Sarawak in the early 1800’s.

“He (Nansian) wants the young generations, especially from the Chinese community, to know and remember the Hakka first settled in Bau before spreading all over Sarawak. I agree with him the centre will enable not only the Hakkas but also the people in Bau and Sarawak, as a whole, to know the history of Bau — how and when the Hakkas came, what they were doing and so on and so forth.”

An area in China where tulou buildings are found.

Ready to take off

On its implementation, Lee believes as long as Nansian is still the Tasik Biru assemblyman, the project will certainly take off.

“This is his idea and I personally believe he will get the funds if he remains in the government. Now, everything is ready. We have the plan and identified the site, and all we need now is funding.”

Lee said the project was ‘very important to not only the Chinese community but also the people in Bau as a whole. He also believes the tulou would be one of the most popular tourist attractions in Bau — as well as Sarawak.

“I think tourists from China will come because they want to see the Sarawakian version of the tulou. You don’t find such buildings anywhere in the world, except China. So if we have one, ours could be the one and only tulou outside China,” he said.

According to Lee, information on gold mining and Hakka history will be exhibited in the gold mine museum.

Anecdotal evidence indicates the Hakkas came to Bau in 1820, setting foot in Sarawak through Sambas, West Kalimantan, to mine for gold and antimony.

While in West Kalimantan since 1700, they organised themselves into several co-operative villages called kongsis, including the famous Republic of Lan Fang near Pontianak, the modern capital of West Kalimantan.

Lan Fang, however, did not survive Dutch colonial rule in what is now Indonesia. Just as the Sambas and Pontianak rulers allowed the Chinese miners to establish kongsis in their territories, the Datuk Patinggis also allowed the Chinese miners to do the same in Sarawak.

When the Sultan of Brunei appointed another Bruneian prince, Pengrian Indera Mahkota, to govern Sarawak and act as the Datuk Patinggi’s superior in 1830, the latter resented his loss of power and led a revolt against the Pengiran.

The then Sultan of Brunei, Omar Ali Saifuddin II, was unable to quell the rebellion of the Datuk Patinggi, which was also supported by the Sultan of Sambas, the Chinese kongsis of Bau (12 Kongsis) and the Bidayuhs who lived around Bau and Kuching.

He, thus, sought the assistance of James Brooke who visited Sarawak in 1839, through his (the Sultan’s) uncle Pengiran Bendahara Hashim.

Hashim promised to give Sarawak to Brooke as his personal fiefdom if he quelled the revolt of the Datuk Patinggi.

Brooke persuaded the Datuk Patinggi to end his revolt and promised him the position of de facto Chief Minister to Brooke, once the Englishman was appointed Rajah of Sarawak.

Brooke, thus, pacified Sarawak, and was rewarded with the fiefdom by Sultan Omar. He became the first White Rajah of Sarawak in 1842.

Brooke and his successors — nephew Rajah Charles Brooke and Charles’ son Rajah Charles Vyner Brooke — expanded Sarawak’s territory at the expense of Brunei’s, and shaped Sarawak and Brunei’s modern-day boundaries.

The site of the proposed Hakka Cultural Village has been identified at the far end of the lake

in Taiton area.

Revolt against Brooke

Rajah James Brooke’s rule was not unchallenged. One of the most serious revolts occurred in Bau in 1857, led by Kapitan Liu Shanbang, head of the 12 Kongsis of Bau, due mainly to high taxes imposed on the kongsis by Brooke’s government.

The Chinese miners were also unhappy with Brooke’s monopolisation of the opium trade, which had benefitted the kongsis. Brooke also tried to monopolise the production of gold and antimony in Liu’s area.

The rebellion began on Feb 18, 1857, and lasted about a week. More than 600 rebels attacked Kuching and the Astana, Brooke’s palace, on Feb 19. Brooke escaped by swimming across the Sarawak River.

The rebels burnt down the Astana and killed five of Brooke’s British assistants. Liu’s rule over Sarawak, however, did not last very long as he did not have the support of the native Bidayuhs, Ibans and Malays who were mostly behind Brooke.

Brooke’s nephew Charles enlisted the help of the Ibans and forced the rebels to retreat to Bau on Feb 22 that same year.

Brooke’s forces later attacked and killed more than 200 rebels, including Liu himself. The remaining rebels fled to Sambas, by now under Dutch rule.

In the 1860’s, more Hakka migrants came to Bau, at the behest of the Brookes. While most of them came to mine gold, others set up shops and also became farmers.

That was a brief history of how the Hakka people came to Bau.

Lee said there was much evidence of the Hakkas’ presence in Bau, adding that Nansian is very keen to preserve the evidence as part of the many tourist attractions in Bau.

“I hope he will be retained for the next election otherwise our dream of having the Tulou Hakka Cultural Centre may not come true. It’s his idea, which we, the Hakkas, not just in Bau but also throughout Sarawak, appreciate so much and would love to see it brought to fruition,” he said.

The Hakka delegates at the main entrance of a tulou.