The book has letters assembled from Wallace’s confidential correspondence to his family and acquaintances.

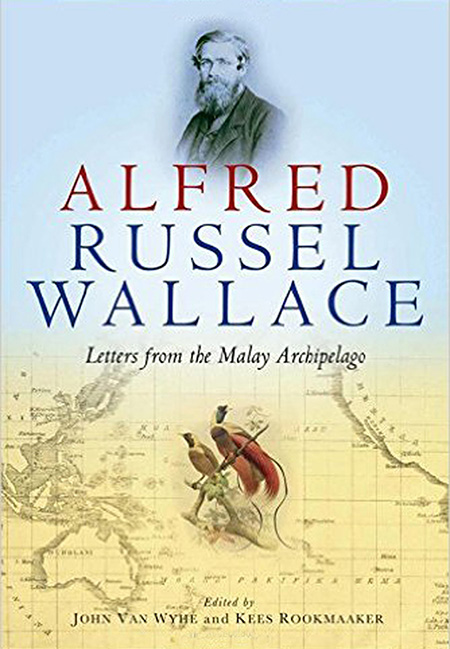

THE opening of the Brooke Gallery at Fort Margherita on Sept 26 prompted me to reread the 2013 publication, edited by John Van Wyhe and Kees Rookmaaker, entitled ‘Alfred Russel Wallace – Letters from the Malay Archipelago’. These letters were assembled from Wallace’s confidential correspondence to his family and his acquaintances in the United Kingdom. I hasten to add that the thoughts expressed in this article are entirely mine and of my own interpretation.

Wallace first met Rajah Sir James Brooke in Singapore in 1854 and was invited to Sarawak to continue his exploration of animal species and to uncover or discover the wonders of Borneo. Brooke was 51 then and Wallace was 20 years younger. Brooke had mellowed much since his arrival in Sarawak 13 years earlier.

There is no doubt that Brooke was a polymath and an amateur naturalist wishing to learn from Wallace. Wallace promptly responded to the Rajah’s invitation and eventually stepped ashore in Kuching in October 1854 after an 11-day voyage from Singapore.

Christmases 1854 and 1855

Both Christmases were spent at the Brooke residency, such was the Rajah’s hospitality and generosity. On Christmas Day 1855, in his letter home to his mother, Wallace enthusiastically revealed many of Brooke’s attributes. By that time Wallace had spent several months living amongst the Dyak.

He found the Dyaks very kind and hospitable and felt that their kindness, moral fibre and orderly lives were the attributes that entrusted Brooke to them.

He recorded that in the years that Brooke had ‘ruled’ Sarawak, there was to date only case of murder amongst the Dyaks and that perpetrated by an outsider. Wallace noted that Brooke was considered as a deity by the interior people and that, “he will be expected to come back again”.

The more time Wallace spent in Brooke’s presence, the more he admired him. This, Wallace attributed to several factors:

- l Brooke’s “highest talents for government”.

- l This was combined with “the greatest goodness of heart and gentleness of manner”.

- l His confidence and determination in placating warring tribal chiefs.

Wallace in the same letter recorded that he saw Brooke’s rule as “a unique case to the history of the world, for a European gentleman to rule over two conflicting races without any means of coercion”.

He also stressed that Brooke “only taxed people with their consent”, thus countering suspicious and ill–informed minds in the UK that Brooke was lining his own pockets. He noted that “Sir James’s private income was spent in the government and improvement of the country”.

This was well vindicated when Brooke returned to the UK and lived a simple and humble life near the village of Sheepstor on Dartmoor, Devon.

According to Wallace, Brooke “introduced the benefits of civilisation” with “a constant check on all crime and semi-barbaric practices”.

Wallace’s letter to his sister

In February 1856, in a letter to his only surviving sister, Fanny, Wallace then in Singapore, stated, “I shall always look back with pleasure to my residence there (Sarawak) and to my acquaintance with Sir James Brooke, who is a gentleman and nobleman in the noblest sense of both words.” Clearly, Wallace was already missing Sarawak where he began to feel at home.

A sketch of a female orangutan from a photograph.

James Brooke – the naturalist

Even when Wallace was in Sarawak writing his famous paper ‘The Sarawak Law’ it is likely that he may have outlined the contents to Sir James. Brooke regarded Wallace’s paper as “a noble act”, for Wallace “to feel the pulse”.

In 1856, whilst Wallace was in Limbok, he received a somewhat politely scolding letter from Brooke telling him he was too cautious about his findings and in the same letter also implied his concern and affection for Wallace.

There is little doubt that Brooke was an avid reader of scientific papers. Whether he understood them or not is another matter.

He could well have been ‘a doubting Thomas’ over Wallace’s findings for he directed Wallace to read the 1856 publication by Baden Powell entitled, ‘Essay on the spirit of inductive philosophy, the unity of the worlds, and the philosophy of creation.’

This letter to Wallace, who was in Singapore, commented on the fact that Baden Powell “adopts your view on transmutation of species”.

Brooke was also in contact with Charles Darwin, such was his interest in the natural world but he regularly informed Wallace of the skins and craniums of pigeons, fowls and wild cats that he dispatched upon Darwin’s request.

It was the paper that Wallace wrote ‘On the Orang-utan or Mias of Borneo’ that provoked Brooke’s letter to the former questioning him on the number of species of orangutan which Wallace had collected in a “limited space of country and should not be therefore be held as conclusive”.

Why did he question Wallace on this matter? It was over what appeared as the simple fact that Brooke in his travels throughout Sarawak and beyond had postulated, as early as 1841, that there was the probability of three distinct species of orangutan in Borneo.

In all likelihood both Wallace and Brooke enjoyed each other’s letters. Later in life when both were domiciled in Britain, they continued to meet up with each other.

We may only speculate about the subjects of their conversations … possibly about the good old days in Sarawak, and no doubt chatted about Wallace’s latest discoveries. Suffice it to say they were both Borneophiles, and visionaries who both had been grateful of each other’s company in hard times during the Victorian era and changed the course of history in their respective ways.

For further investigation into Wallace’s letters go no further than the aforementioned book, now published in paperback form in 2013 by Oxford University Press (OUP).