Visitors walk along the beautiful wooden walkways.

BEYOND the bustle of Orchard Road shopping malls, eating places, museums, art galleries, temples and churches in Singapore, I wonder, when visiting this most densely-populated country in the world, how many of us go further afield?

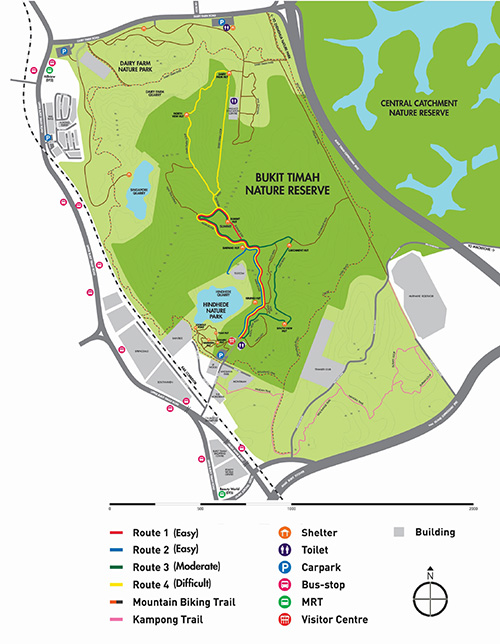

For a short taxi or MRT ride away lies a very accessible countryside world at Bukit Timah. It is so near and is an oasis for nature-loving folk.

I first stayed in Bukit Timah for a week in 1994. Last October, I returned for a family foray to Bukit Timah Nature Reserve (BTNR). It was the very weekend after BTNR was officially reopened to the public. It had been closed for two years to allow the restoration and rebuilding of footpaths, and to afford greater protection for the flora and fauna.

The footpaths had become degraded and slopes eroded but the restoration project has allowed Singaporeans to experience a local ‘urban lung’ with exceptional biodiversity. With a total area of 163ha, BTNR, also classified as an Asian Heritage Park, has over the years seen annual visitor numbers increase from 100,000 people in the mid-1990s to 400,000 in 2014. No wonder it needed a facelift.

Meaning of ‘Bukit Timah’

As a Cornishman by birth, from a tin mining environment, with a small Bahasa Malaysia vocabulary, I thought I was right in translating Bukit Timah as ‘tin bearing hill’. As this hill is made of granite and, like the granite in West Cornwall, which once contained exploited veins of tin ore, this seemed a plausible translation.

Others suggest that ‘Timah’ is a vulgarised version of ‘Temak’, a tree found in primary forests and subsequently mispronounced as ‘Timak’. Other etymologists suggest that it is a shortened, familiar version of Fatimah. Who really knows? Perhaps it is the buttress roots of the trees (pokok temak) that are still so obvious today that gives Bukit Timah its name. All will agree that it is a site well worth visiting.

Nature has reclaimed the former Hindhede quarry, which is now a reservoir.

History abounds

The rich biodiversity of its forest cover goes back well before mankind’s occupation of our planet and this habitat is still with us today. In the 19th century, Indian convict plantation workers farmed areas of this estate. Sadly, by 1860, nearly 200 workers had been killed by tigers. These tigers had swum across from Johor, no doubt attracted by the colonial government’s decree in 1848 to grant protection to Bukit Timah’s primary forest.

Even at that time, there was fear of over-logging and the gradual depletion of timber resources. Cavenagh, as governor of Singapore in 1859, arranged patrols of this forest area to eliminate tigers. In that year alone, six tigers were shot. Bukit Timah subsequently became Singapore’s first declared nature reserve with granite quarrying allowed to continue, under licence, in parts of the reserve, up until 1990. Hindhede, a Danish civil engineer, started his granite quarry there in 1922.

The Second World War saw a brutal but short-lived battle at Bukit Timah, for at 163.63 metres above sea level, that hilltop was the highest and most strategic point on Singapore. Today, on the walking trails, a commemorative plaque exists as a memorial to those fallen Malaysian, British, Indian and Australian soldiers.

With the Imperial Japanese occupation, albeit short-lived, this nature reserve was not neglected. Japan, after all, had established many natural reserves and parks in the early 19th century and was the first country in the world to recognise the needs of its people to go close to nature and to designate national parks as protective areas. During the Japanese occupation, distinguished botanist Professor Kivan Kobe from Kyoto University was posted to Bukit Timah to oversee the reserve’s botanical and zoological protection. In 1951, this reserve came under the protection of the National Parks Act.

BTNR today

BTNR today

My afternoon’s foray with my family, including a seven-month-old grandson, started at the Visitor Centre, only a short walk from the carpark. There, a well-documented exhibition with detailed maps of the various trails displayed the reserve’s wonders. I took the Hindhede Trail along most beautifully crafted walkways, guided by delightful handrails. The quality of the craftsmanship has to be seen to be believed.

All the walking trails possess hard but non-slip surfaces, allowing rainwater to percolate through to the plant roots below. Thick rope handrails not only help older folk up steeper sections but also act as passive guides. Swampy areas are navigated over fibre-reinforced plastic walkways, keeping one’s feet dry but as importantly protecting the wildlife beneath.

At the summit of the trail, on a large viewing platform over Hindhede quarry lake, man and nature gel, for the quarry’s granite rock faces are exposed pointing up to the summit of Bukit Timah. There, the distinctive beauty of the canopy of the emergent trees in the primary forest caught my eye together with their stalwart buttress roots.

Hindhede Quarry Lake is the product of deep granite quarrying down to a depth of 30 metres below sea level. Since quarrying stopped in 1990, this depression has filled with rainwater, and with a depth today of 32 metres, is now a reservoir, which in 2008 over-spilled.

Nature has certainly reclaimed Hindhede quarry, albeit in such a short time and in such an urban environment.

Wildlife

On the trek up to the quarry, I saw numerous species of birds yet one caught my fleeting attention – magpie in colouring but with a dash of red near its beak.

The downhill trail proved more exciting for I bumped into seven amateur wildlife cameramen with their sited tripods and long lenses. Inquisitive as I was, I asked them what exactly they were photographing. It was a tree viper. Seeing it sense my approach with its tongue flicking, I beat a hasty retreat with a blurred photo!

Lower down, another cameraman pointed out a flying lemur clamped to the trunk of high tree. This animal is, in fact, not a lemur but one of the squirrel family. Lastly, I caught sight of a mouse deer as twilight was approaching.

The Raffles Hotel is often quoted as ‘the grand old dame of Singapore’ but for me the ‘grand old lady of biodiversity in Singapore’ is none other than the BTNR.

I know that I shall again visit this easily accessible rainforest environment and continue to marvel, close at hand, to view our natural world, for there is much there that I have yet to discover. My few hours there to view the flora and fauna was a lesson to see conservation and preservation at its very best.

When next in Singapore, do spare time to visit BTNR for it will be time well spent.

The buttress roots of the Temak tree could be what gave Bukit Timah its name.