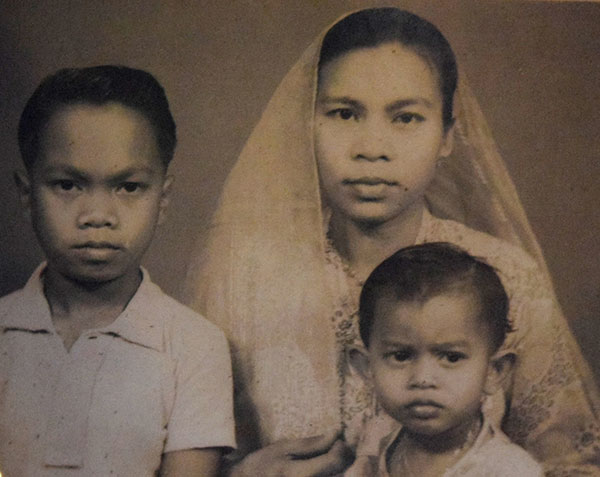

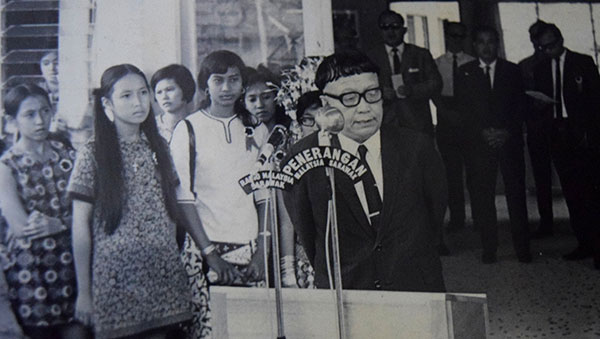

Linyang continued to be attached to the Iban community and took part in Iban community functions and events, bringing along her two children. Here, they listen to a speech by Tun Temenggong Jugah during the opening of Rumah Dayak in Miri.

IT is amazing how neigbhours, friends, relatives and acquaintances can come together and appreciate impactful lives which add meaning to a community.

These stories are the oral traditions which provide us with real social values and especially traditional knowledge like patterns of textile weaving, basket and mat weaving.

These are passed from mother to daughter, from aunt to niece, from father to son.

Most forms of traditional knowledge are passed through stories, legends, folklore, ritual, songs and family genealogy. These are valuable information we should record and collect in Sarawak, especially when they are made available.

And an African saying — When an old man dies, a library burns to the ground — is the inspiration for the writer’s lifelong journey in recording oral history whenever the opportunity arises.

Sarawak in the 1940’s saw migration of Ibans from Sri Aman and other Iban ancestral homes to Miri, Bintulu, Marudi, Brunei and even Sabah.

Furthermore, Sarawak also saw in-coming migrant workers from India and Malaya who were encouraged by job opportunities offered by British East India Company in the Far East.

While there were unspoken rules about the Chinese not given the right to legitimately marry native women, many Chinese-native ‘unofficial marriages’ occurred before and after the Second World War, especially when Chinese men could not find suitable Chinese wives locally or afford a mail order bride from China.

Studies have been made on these unions by Chew and Langub of Unimas.

There were no laws against other races like Indians, Malays, Burmese and Indonesians marrying local wives during the colonial days. And, of course today, multiracial marriages are even lauded.

According to a relative who married an Indian, many differences have to be understood to bring about a harmonious marriage.

However, sharing the same religion and spoken language makes a lot of difference and eases communication issues. Thus, it is quite common in Sarawak to have inter-racial and inter- cultural marriages which have shared religion and shared language.

A marriage counsellor told thesundaypost: “Conflicts, however, may occur due to inter-personal and intra-personal relationships, not so much on cultural and racial issues.

“However there are other factors to take into consideration to develop a really fine marriage based on two races. Quite often, the fear of multiple problems may lead a couple who are very much in love, to break up painfully before the marriage stage.”

Unique story

When discussing multiracial marriages, she herself was very impressed by the long-lasting marriage of Linyang and Abdul Basha.

How did the inter-racial marriage of Linyang Sulong and Abdul Basha leave a mark on the social tapestry of Miri in particular?

Definitely, here is a unique story of an inter-marriage of an educated Muslim Kerala Indian, who later became Bahasa Malaysia speaking, and a small, beautiful unschooled, Iban woman who could only speak Iban.

Abdul Basha came from Kerala with his siblings to work for the British East India Company in Miri before the Second World War.

Linyang Sulong, on the other hand, had migrated from Sri Aman to Beraya with her relatives. She was widowed with a little son.

Fate brought the two together through Linyang’s police field force cousin who said: “Abdul Basha is a good man. He will love your son and you. He respects people and is hard working. He may not have the good looks of your other two suitors.”

Linyang had two other suitors — a Eurasian man with good looks, and a Malay man who was equally good-looking.

“However, she had to further make a difficult decision because she had to convert and become a Muslim” according to a close relative.

Miri was already a melting pot in those days, noted one of Linyang’s friends Mrs Zaini, now still living in Miri, and often meeting up with Linyang’s daughter, Jamila Abdul Basha.

Mrs Zaini told thesundaypost: “For so many years we — Linyang or Mak Jamila — and I had been very close friends. Mak Jamila was friendly, and helpful. A good friend, indeed, amongst the ladies. She was a tailor and having a most cheerful personality. She was always contributing to the Shell employees’ social gathering.”

Mrs Zaini was married to a Shell staff member and interacted closely with Linyang and family as Abdul Basha was also employed by Shell after his stint with British East India Company.

An Indian and Iban Inter-racial marriage of the 50’s was probably a new social phenomenon then. And most people were interested in getting to know the friendly and helpful Abdul Basha and his hard-working Iban wife who planted vegetables around their house and did Iban mat and pua weaving.

Abdul Basha was injured during the war and he was left with a badly maimed left arm. Shot and wounded, he had a shoulder-bone protruding from the body.

The injury left him with little flesh on his arm. Linyang, although she could not read and write, learned tailoring by herself and made shirts for her husband. No one would know about his maimed arm because she cleverly made padding for the shoulder and sleeves!

“How did she know about making a shoulder padding? It was even before the shoulder pads became popular in the 60’s. My mother was really imaginative. I’m glad she taught me so much about tailoring,” her daughter Jamila said.

Nyonya kebaya

Jamila related her mother just thought of ways to make beautiful clothes. One of her mother’s accomplishments was using sewing machine, bought by her father, to make ‘baju draw’ or the Nyonya embroidered kebaya, using the original kain kasa robiah.

These baju kebaya patterns have been left as legacies to her daughter, daughter-in-law and grandchildren.

Linyang herself came from the stronghold of Ibans in the Second Division. Most of her relatives are from Batu Lintang, Undup and Munggu Demari.

While her husband Abdul Basha was a strong technical man, she was a good housekeeper.

Abdul Basha was loving towards his stepson Bujang and provided very well for Linyang, like buying a piece of land and building a house in Pujut 8, Miri. He was thoughtful and was good to all her relatives who came to visit. He also kept a very good garden, besides being a good handyman.

Jamila said her mother gave her and her brother very important Asian values in life. First, they were trained to be careful with money. Her mother, always resourceful and very frugal with allowances for the family, would also make kuih from scratch.

Jamila is glad she has learnt so much from her mother that she does some catering business from time to time. She herself also never has to buy cakes, kuih and snacks for her family and she has, in turn, taught her daughters all the culinary skills.

“My mother was always learning from other women, wives of Shell employees in Lutong and neighbours, in those days. As a result she became a very good cook, and mastered Indian, Iban and Malay culinary arts.

“Today my her sister-in-law and I cook Indian curries as well as Malay and many other great dishes taught to us by my parents, Indian relatives, Iban relatives, Malay friends.

“My mother’s special skills of food preparation, meticulous knife skills, and specific tastes have been passed to me and my sister-in-law,” Jamila added.

Another legacy

Linyang left another legacy to her children and grandchildren. Before she passed away, she made many beautiful samplers of mat weaving designs.

Although Linyang was not a weaver-instructor or renowned master-weaver, she had cleverly designed on her own the right pedagogical designs, easy step-by-step patterns for anyone to learn about Iban Mat and pua kumbu weaving.

These models have been preserved by Jamila carefully. Photographs of these designs could even help someone write a book on Sarawak mat weaving designs!

Linyang, in her later life, after her husband passed away, went on the Haj alone, not accompanied by any Muslim relative. And she had also visited India once with her daughter and husband for a whole month. These two trips must have been great berjalai or journeys for her.

Another relative remembered her as a healer to many of her fellow Ibans who had migrated from Sri Aman area in the 50’s and 60’s. Healing skills have to come from the ancestors and not every Iban has them.

Linyang’s grandfather, a special healer had given talismans to Liyang which she used appropriately to help many women and men get well.

She also told thesundaypost that Linyang used a kind of wood from the jungle and some oils to heal her mother.

In return, after three days, her mother was totally cured. In token, her mother gave Linyang a coin, and a small knife.

While recalling many good stories about Linyang, she also related that Linyang, true to Iban tradition, did not commercialise her powers.

“Linyang did not claim she knew everything and could cure an ailment. She just said she would look into the matter and see what she could do. She also had dreams which told her what to do. ”

Brave and independent

A long-time friend, Jim Dallas, an American Peace Corps volunteer, who taught in SMK Lutong in the 60’s, wrote to the writer: “Mak Jamila was an amazing woman who was candid, friendly and cheerful. She was really good in communication. I was really impressed by how she could get people to laugh and converse congenially. She was a brave and independent woman.”

Dallas, after leaving Sarawak for more than 40 years, could still remember very vividly sitting next to her in a bus and how cheerful she was meeting her friends and a ‘big American teacher’.

He wrote: “My first introduction to Jamila’s mother occurred when I left the bus to enter a house across the road coming from Lutong going to Miri.

“In the distance, Jamila’s mother was calling me to visit.

She was very aware how often I visited her neighbours. She did not want to be the last on my list of visitations. She would remind me of how many times I visited other homes.

“I formally met Jamila’s family during Hari Raya that year. Her dad and mom were gracious and I had the distinct impression that mom ran the home.

“She was a strong woman who promoted her children. Jamila is a modern version of her mom. Both were women libers in a village where women led a more passive role in the face of a Muslim tradition. When I see Jamila, I see an Indian woman with Iban eyes and Iban stature. Their family (then) was low income but hard-working and blessed.”

Dallas continued: “I remember her mom really wanted a better education for Jamila who was then 16 or 17 years old. And this is a mother who had her daughter’s education and future at heart, probably even thinking of matching her with an orang putih! Later Jamila gave me an Iban pua kumbu made by her mother. I will always remember her mother.”

Many people have been touched by the lives of Mak Jamila and Abdul Basha of Lutong. It is amazing how their ordinary examples have become awesome because they went out of their way to share their knowledge, to help their neighbours raise their hopes and dreams, to help others in need and to contribute to their community, through their own hardwork, through their children and their grandchildren.

A fellow teacher and long-time friend of Jamila, remarked: “In our small community, we learned much from Abdul Basha’s family. In a way, we developed together an open communication, learned more about Iban and Indian cultures. We are richer because we have interacted with people from diverse backgrounds.

“Yes, in a way, if we seek to understand others, we have inner peace and greater depths in our life.”