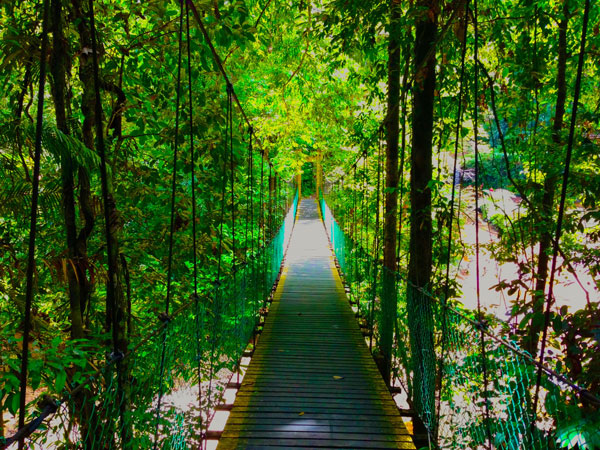

Those with sure footing and a head for heights can explore the canopy walk. — Photo by Nicolai Edgar Andersen

LAMBIR Hills National Park celebrated its 40th anniversary last year. It is Sarawak’s fourth oldest national park after Bako, Gunung Mulu and Niah.

Sixteen years ago, I first visited the Lambir Hills to explore the possibility of taking geography and biology students from the United Kingdom there on future fieldwork expeditions. Four months earlier, I had led a large group of students for three week’s field work in Sabah at Mount Kinabalu National Park, to the summit of Low’s Peak and in Danum Valley.

To my surprise Lambir Hills, lying 32km southwest of Miri on the Miri-Bintulu road, proved to be one of the most accessible national parks in Malaysia. With only a 40-minute drive from Miri and frequent bus services, it is so easy to find.

In 2000 and on a weekday, there were hardly any visitors in the park, yet, in subsequent visits, I found that this once relatively unknown national park attracted many Miri families to enjoy their local ‘green lung’. Many school field trips now visit as well as trainee teachers and others studying environmental sciences.

At weekends, Lambir is a hive of activity for family picnickers enjoying the scenery of the wild-scape and trying to catch a glimpse of its native dwellers, be they animal, vegetable or mineral.

The setting

The Lambir Hils are made of sandstone, in a particularly friable form, which breaks down easily to produce various types of siliceous (acidic) soils with rugged sandstone cliffs on the edges of the park. Beneath the sandstone are underlying thick shale deposits, suggesting that both rock types were once massive river deposits in shallower seas when suddenly plate tectonic movements thrust these rocks up out of the seabed.

This national park holds 25 per cent of all East Malaysian tree species in its 6,952ha of lowland dipterocarp forests, with heath forests or scrubland (kerangas) rising on the barer sandstone exposures to the summit of Bukit Lambir at 465 metres.

This relatively small national park is home to over 2,000 tree species, 237 species of bird, 64 types of mammal, 46 species of reptile, and now 20 species of frog. Twenty per cent of the tree species are rare and found only in this area.

At the time of writing, I am sure that many more species will have been observed but not yet registered. This truly is a national park of national and state importance.

International interest

A joint project sponsored and developed by the Forest Department, Harvard University and three Japanese universities (Kyoto, Osaka City and Ehimi) established a 52ha field station within the park for ecology students to study a tropical rainforest environment at first hand.

Over the years, many of these postgraduate research students have identified numerous species of dipterocarp trees, noting that 33 per cent of all Sarawakian species are contained in this small research enclave. Further afield, but within the park’s boundary, they have identified an amazing 80 per cent of known types of fig tree.

Why such biodiversity at Lambir in such a small area? During the Ice Ages (1.4 million to 10,000 years before the present) the South China Sea was part of a landmass, for sea levels had fallen as water was retained in huge continental ice sheets and the one-time sea floor was covered by forests.

As the ice melted, so the sea level rose, thus leaving pockets of isolated forest on higher land. These ‘islands’ of forest allowed further species to evolve in relative isolation from each other thus leading to the biodiversity of today.

Such an example is a particular type of dipterocarp tree found in this national park. The Dryobalanos lanceolate has a trunk of over three metres in diameter with its lowest branches at 50 metres or more above ground level.

To identify this tree at Lambir, look out for its six-metre high buttress roots and then look upwards to its canopy spread of over 10 metres. This is, indeed, a giant emergent tree specimen.

Today there are three tower platforms of between 30 and 40 metres high from which visitors can observe the canopy wildlife and in particular the orchids, tree ferns and other epiphytes as well as the bird and insect life way above ground level. Those with sure footing and a head for heights ought to venture onto the canopy walkway.

Visitors can cool down at several waterfalls after a good trek.

Spectacular waterfalls

Within a short walk from the headquarters, there is the resplendent Latak waterfall, surrounded by rock-walls and plunging down 25 metres into a pool. This plunge pool is ideal for swimmers to cool down after a good trek amongst the forest trails and where to change clothes before their departure. It is rumoured that seven princesses live there to seduce male bathers to visit the plunge pool.

I must admit that I never saw even one princess as I changed out of my sweat drenched T-shirt and into my swimming trunks to enjoy the coolness of the Sungai Lambir waters and a shower in the plunge pool.

The Latak waterfall is one of several safe for swimmers, with another just below the summit peak. There are 13 well-marked coloured routes along a central path with branching interlinked trails. These routes range from a 12-minute walk from the park headquarters to three and a half hours to the summit of Bukit Lambir, over a distance of 6.3km but uphill.

Protection of species

An independent report, eight years ago, declared that the sun bears, numerous species of hornbills and Bornean gibbons which this national park once housed were no longer to be seen, through illegal poaching and a considered lack of law enforcement.

This has now been addressed through the ever-increasing vigilance of the park rangers.

However, the present El Nino event, the strongest recorded in human history and even worse than that of January to mid-April 1998, could well adversely affect plant, animal, and insect habitats at Lambir.

This seasonal and tropical dipterocarp rainforest depends upon the germination of seeds under the canopy shade of the taller trees.

Sadly, in 1998, the fig wasp (Agaonidae) population – the pollinators of fig plants – were wiped out with the consequent reduction in the number of fig plant species.

The professional researchers at the field station will no doubt publish their findings, given time, as to the consequences of the 2015-2016 El Nino at Lambir.

This is a most welcoming national park and truly a sight to behold, with many memories to keep on its rare biodiversity.

With manageable walks it offers an excellent day out for all family members of all ages to appreciate the natural wonders of Borneo.