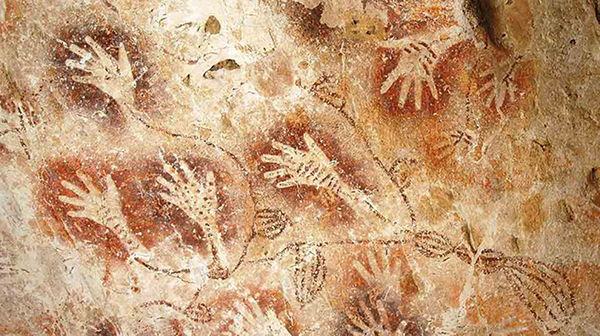

Groups of stencilled hands arranged in a fan-like fashion were discovered in the Marang Mountains of Eastern Kalimantan. – Photo by Luc Henri Fage

PRIMITIVE art has always fascinated me, especially prehistoric cave paintings. The images painted on cave walls of animals and hominoid forms reveal much about the local environment in which early man lived. From both anthropological and artistic viewpoints, such paintings point to the implements and paint mixtures that these early artists used.

Based upon extensive research, Dutch palaeontologists Professor Wil Roebroeks and Dr Marie Soressi at the University of Leiden recently published a paper in which they maintain that Neanderthal folk were as intelligent and as inventive as their successor Homo sapiens. Moreover, early man appears to have had a trial and error knowledge of basic chemistry.

The word ‘Neanderthal’ was first coined in 1857, derived from a humanoid skull excavated in the River Neander valley near Dusseldorf, Germany. Near this anthropological site there is evidence that early humans used fire to turn stripped birch bark into bitumen and then to distil the latter into a glue with which to attach stone arrow heads to elongated shafts to create spears.

The Bruniquel limestone caves, in the Aveyron Valley in Southwest France, have revealed the creation, by Neanderthal people, of four stone rings laid out in circles and half crescents, made of broken stalagmites. So deep in the cave system where these are located that Neanderthals must have had fire to light torches to see what they were doing some 186,000 years ago.

A Neanderthal cave in Croatia has revealed a necklace made of the talons of eagles whilst other finds in caves in Spain and Italy unearthed coloured seashells painted with ochre (clayey) pigments. It is now thought that some of the earliest cave paintings of handprints and animals were the work of Neanderthal man using blocks of manganese dioxide.

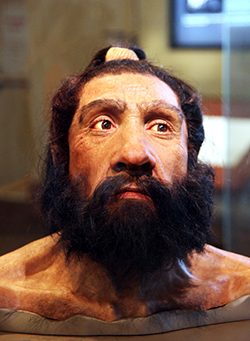

A model of a Neanderthal adult male is seen in the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History in New York.

Demise of Neanderthal man

The Dutch researchers maintain that these humanoids died out not because they were overcome by Homo sapiens, who arrived in Europe from Africa and the Near East 40,000 years ago, but because of several interrelated factors.

These included the initial low density of the Neanderthal population, interbreeding with Homo sapiens peoples, hybrid sterility amongst Neanderthal men, genetic swamping and assimilation by these new immigrants.

It is thought that Neanderthals lived together with Homo sapiens for 2,000 years or more. Through the interbreeding of the two species, most people today owe at least 1 to 4 percent of their genes to this extinct species of mankind.

European cave paintings

Caves in karst (limestone) scenery have provided shelter for both animals and humans to escape the ravages of inclement weather and climatic conditions over the centuries. The most famous prehistoric cave paintings in Europe, discovered in the 20th century, are those in the French departments of Dordogne and Lot-et-Tarn.

In 1940, an adventurous schoolboy discovered the now famous Lascaux Cave, dated as 17,300 years old, and depicting ibex (goats), bison, horses and wild oxen. In 1979 these caves were declared a Unesco World Heritage Site.

As a tourist honeypot, thousands of visitors annually frequented these caves, so air conditioning and high intensity floodlights were installed but, combined with human breath, disaster struck. Sections of the murals were attacked by mould in the form of a grey or black fungi. Quite rightly these painted caves of Mesolithic origin are now closed to tourists but a replica cave has been built to include duplicate images of the original paintings.

The outside of the Bruniquel caves (mentioned earlier) revealed 20,000-year-old mammoth and deer bones and again it was a local boy who, with the help of others, unblocked the caves’ entrance to explore yet deeper inside.

In one cave there are wall paintings of deer, goats, horses, black bison and reindeer, suggesting that these were painted towards the later stages of the Ice Ages, dated at between 42,000 and 15,000 years ago.

A horse from the Panel of the Chinese Horses from the Lascaux Cave. – Photo by Ministère de la Culture et de la Communication, France

Sarawak’s cave paintings and artefacts

Closer to home, and fortunately, the Painted Cave at Niah allows limited access to daily visitors in order to preserve the prehistoric art works of birds, boats and prancing figures, probably of hunters or warriors.

The images of boats are in fact those of death ships or coffin boats. The remains of actual coffin boats found here are aligned towards the centre of the cave. It has been established that early man occupied these caves as long ago as 50,000 years before the present in Middle Palaeolithic times until about 5,000 years ago in Neolithic times. These were early Punan people.

Similar coffin boats, but made of iron wood, are seen today at Coffin Cliff in the Danum Valley in Sabah, where Kadazandusun people buried their dead. In my two visits to Coffin Cliff, I have climbed the frail ladders to peek into a cave to see tiered layers of coffin boats whose occupants have been laid to rest for centuries.

Interestingly, the Njadhu people of South East Kalimantan continue to practise the coffin boat cult and it is thought that their art and folklore are closely related to the scenes painted on the walls of the Niah Painted Cave.

Eastern Kalimantan and South Sulawesi

Frenchmen Luc Henri Fage and Jean Michel Chazine, both leading experts in their respective fields of speleology and anthropology, led a French/Indonesian expedition in the late 1990s to discover cave paintings in the high level but small caves in the cone karst country of the Marang Mountains of Eastern Kalimantan.

These paintings have been dated as between 35,000 and 40,000 years old. In several caves they discovered groups of stencilled hands arranged in a fan-like fashion and painted in outline in various natural pigments from black to bright red, the black made from charcoal and the yellowish to red colours from local clays.

It is thought that paint was sprayed over human hands, placed against the cave wall, to provide the stencilled outline by squirting the paint from the artist’s mouth and blowing it through a reed.

This perhaps was the earliest invention of the air brush. Some hands were overpainted to reveal delicate fingernails and others displayed a series of black dots not unlike those found in aboriginal paintings in Northern Australia.

On other cave walls and roofs anthropomorphic and zoomorphic shapes were seen in the form of antlered reindeer and wild buffalo and matchstick-like human figures with large heads and feet and long billowing hairstyles. In the Marius region caves of South Sulawesi ‘paw prints’ of birds (with three digits), reptiles (four digits) and monkeys (five digits) were observed.

Today’s primitive art

Yesteryear’s primitive paintings are still alive today in many homes where parents treasure their child’s first drawing or painting. Mums and dads are usually drawn with matchstick bodies and limbs but with big faces, hands and feet and a mop of hair. At playschool or kindergarten, children are proud of their coloured handprints decorating the walls with their names, usually written by the teacher, under each print.

It is interesting that Neanderthal and Palaeolithic artists never painted the vegetation and landscapes surrounding them but, undoubtedly, they were the forerunners of the 19th century Impressionist art movement, giving us a historic glimpse of the most important things in our lives today – food and friendship – albeit in different climatic times.