Regarded as being far ahead of her time, Datuk Ajibah Abol bequeathed to the younger generation, especially women, the value and pride of struggle, the courage to rise and the priceless power of knowledge

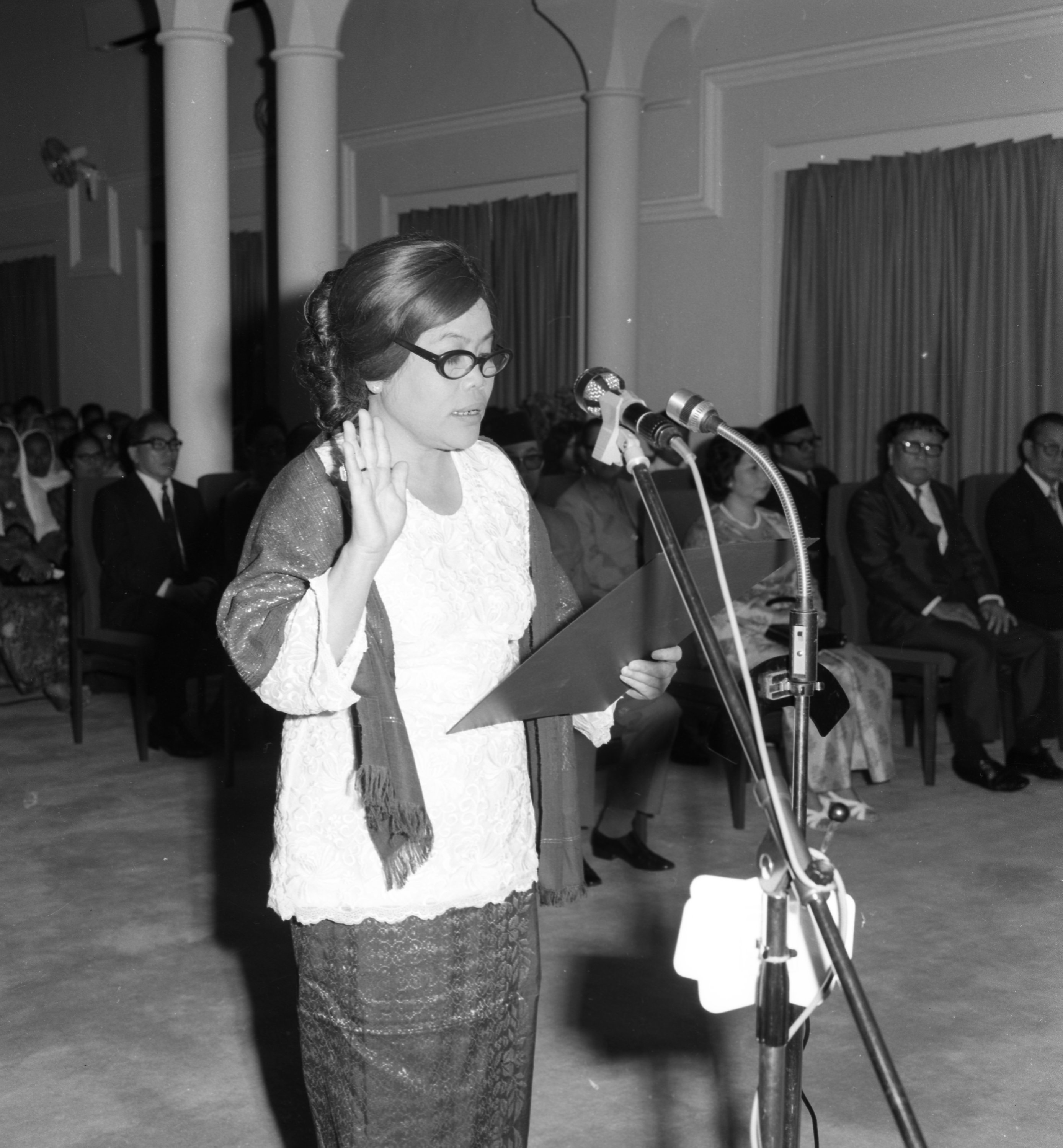

Ajibah reciting the oath at the swearing-in ceremony held at Astana Negeri after her victory in the 1974 state election.

AT a time when Sarawak women tended to shy away from politics, Datuk Ajibah Abol emerged as the first woman to stand for the state election in 1969. Her landslide victory paved the way for her to become the state’s first woman minister in 1970. It was a major breakthrough that made history for Sarawak women.

After her untimely death in 1976, she was posthumously conferred the Panglima Negara Bintang Sarawak Award by the state government, making her the first woman in Sarawak to be honoured with the title ‘Datuk’.

Her narrative encapsulates the hopes and hardships of women in an era when gender bias in society did not work in women’s favour – a problem that lingered for many years before being gradually resolved by the mid-20th century. Ajibah thought that women were capable of taking on leadership roles and duties in order to serve the country, and that they should not succumb to the ‘irrational’ view of her time that their function was limited to serving their families at home.

Anti-cession union

Born in 1921, Ajibah was 26 years old when she joined her former teacher and colleague Lily Eberwein in setting up the women’s wing of the anti-cession Malay National Union (MNU), ‘Wanita Persatuan Kebangsaan Melayu Sarawak’ (PKMS), on March 16, 1947, as a direct response to the handing-over of Sarawak to the British Crown by the third White Rajah. At the inaugural meeting of the women’s wing, which was attended by over 1,000 women, she was elected secretary, while Eberwein was the chairwoman.

The story of the struggle and rise of women in politics began and sprung forth within the historical framework and against the backdrop of the anti-secession period. It was the beginning of Ajibah’s political career.

She looked up to Eberwein, a patriot and pioneer for women in public life, as a mentor, one who influenced and shaped her to become a people’s leader.

When the Brooke-led government opened the Permaisuri Malay Girls’ School in 1930, Eberwein was its principal and Ajibah, who was only nine years old then, was among her first students.

When Ajibah’s father, Bolhassan – more popularly known as ‘Abol’ – decided to send his daughter to school, he raised eyebrows among the conservative parents.

Ajibah considered herself as fortunate to be able to attend school, despite growing up in a neighbourhood where the conventional view was that a girl’s place was in the kitchen.

She was a good student – one who took her studies seriously. However, after completing her primary education, she had to stop schooling to allow her younger siblings to attend school. As a postman, Abol’s income was meagre and he struggled to give education to all his children.

Ajibah (left), the then-Minister of Welfare, Youth and Sports, chatting with Datuk Hafsah Harun who was then the honorary-treasurer of Sarawak Federation of Women Institute. The picture was taken just a week before Ajibah’s untimely death on July 15, 1976. After Ajibah’s death, Hafsah contested in the former’s constituency and won, and was later appointed an assistant minister in the Sarawak Cabinet – before being promoted to a full minister.

Breadwinner of family

The second child in the family, Ajibah sacrificed her educational pursuit to ease her father’s financial struggle. Upon reaching the age of 18, she took up teaching at her alma mater where she worked with her former teacher, Eberwein who was the principal. With a monthly salary of 30 dollars (the currency used in British Borneo then), she soon became the breadwinner of her family, following her father’s retirement.

Her natural sense of sacrifice stayed at the forefront of her mind. When Sarawak was ceded to the British Crown in July 1946, she made a significant choice of opposing the cession, even if it meant resigning from a secure post at a government school.

Together with Eberwein, Ajibah was among the hundreds of government servants who resigned from their jobs as a response to the famous Circular No. 9/1946.

The circular, issued by the colonial government, warned that all government employees who associated themselves with anti-cession activities and other acts of disloyalty to the government would render themselves to instant dismissal.

The two women gave up their jobs a month after the Wanita PKMS was formed. Ajibah became actively involved in the anti-cession movement, participating in demonstrations and sending rejection letters and appeals to the colonial government. She worked shoulder to shoulder with her male counterparts in the PKMS, who were mostly prominent Malay leaders.

Setting up private Malay schools

With teachers forming the largest number of civil servants who resigned from the government, one-third of Malay government schools were forced to close down. This prompted Ajibah and the others to set up private Malay schools to cater for children whose parents were no longer in the government. Ajibah volunteered to teach in one of the schools.

After the cession controversy had quietened down, many of the civil servants who had resigned resumed their jobs in the government. However, Ajibah was determined to spread her wings and venture into politics.

Through her active involvement as a young activist in the anti-cession movement, she had built an interest in politics. Explicably, it had heightened her spirit of patriotism that she felt called to be in politics to pursue the common good.

Still volunteering in the private Malay school, she had also started a kindergarten at her house in Kampung Masjid in Kuching. A single, independent woman in her early 30s, Ajibah’s calibre as a leader was unmistakable. Soft-spoken, gentle and polite, she connected with people from all strata of society. She was characteristically gentle, and yet, firm in her conviction.

Ajibah meeting the residents of Kampung Panglima Seman, near Kuching, during her official visit to the Malay village in 1974.

Founding chairman of women’s wing of BARJASA

Ajibah was a key figure in the formation of the political party, Barisan Rakyat Jati Sarawak (BARJASA) in 1961, and the founding chairman of its women’s wing. Her commitment to the party was unquestionable as she steeled herself for new challenges ahead.

There were times when she had to deal with the difficulties of working in a male-dominated territory and was able to rise above the hurdles with admirable resilience. She displayed such grit in the face of challenges and difficulties that she was laudably nicknamed the ‘Iron Lady’.

When BARJASA merged with Parti Negara Sarawak (PANAS) to form Parti Bumiputera in 1966, Ajibah was another step forward. She was elected as co-vice chairman of the party as well as the vice-chairman of its women’s wing. She made history for Sarawak women when she stood for the 1969 state election — and won.

“There’s no stopping women to take leadership roles to serve the country,” she would say as an encouragement to other women. As if demonstrating her point, she was appointed State Minister of Welfare and Culture in 1970, at age 49.

Sarawak’s first woman minister had continued to focus on social change and progress in the state until her untimely death in 1976.

Ajibah retained her seat in the 1974 state election, a year after Parti Bumiputera merged with Parti Pesaka to form the Parti Pesaka Bumiputera Bersatu (PBB). After her victory, she founded the women’s wing of PBB and became its chief.

‘A matter close to her heart’

Ajibah seemed to be racing against time in her efforts to help bring about social change. During her first year in office, she set up the Koperasi Wanita Kuching, a cooperative thrift and loan society to encourage the habit of saving among Malay women. She also helped raised funds for Wanita PKMS to build their headquarters at Jalan Muhibbah in Kuching.

The welfare of rural women was a matter close to her heart. She made frequent visits to the rural areas, going to remote villages to meet with the people and see for herself their living conditions and what needed to be done to improve their well-being.

Her genuine concern for the people was best described by Maimumah Daud, a journalist who had worked closely with the minister: “During the years of working together in the Wanita PKMS and Koperasi Wanita Kuching, Datuk Ajibah never forgot her responsibility as a leader. Any problem, big or small, that had to be solved, she tried to do her best to solve them with that special brand of gentleness that was her trademark.

“She was so deeply schooled in discipline and good manners that to be outspoken or to raise her voice over issues was not her style. She believed in healthy discussions at meetings where she would invite all members to voice their opinions on a given subject and chair with gentleness and firmness.”

Ajibah had the people’s welfare at heart. Even after becoming a minister, she still opened the kindergarten that she started at her home. In addition to that, she hosted religious and literacy classes at her home to cater to the village community.

In the midst of her heavy schedule, she never failed to show her concern for the people. Days before she succumbed to heart attack, she was visiting a few villages in her constituency to supervise the distribution of water to the village folk.

Kuching had been in the grip of a dry spell and the minister wanted to make sure that everybody had their share of water. Her physical presence at every distributing point was to give moral support during the difficult time.

Alas, it was to be her last official duty. Four days later, on July 15, 1976, Ajibah died of a massive heart attack.

The first woman minister in Sarawak walking beside Datuk Stephen Yong, then the Deputy Chief Minister of Sarawak, in 1974.

Desire for more educated women in politics

In an article in ‘Sarawak Gazette’, Maimunah Daud wrote: “Her dearest wish was to see more educated women in Sarawak take the lead in state politics.

The late Ajibah confided that she was disheartened to note the reluctance of our young women with leadership potential to serve the country. She spoke of her desire to groom those (whom) she recognised to have leadership qualities, but she needed time to convince these ladies that commitments made in the interests and well-being of the ‘rakyat’ (people) and the nation were worth all the sacrifices. But this was not to be. Fate stepped in and changed everything.”

Ajibah’s aspiration to groom younger women with leadership qualities to be future leaders did not come through, but she had left behind a legacy of personal sacrifice and true leadership. Hers was a selfless lifelong commitment driven by her undivided love for her people and country.

Ajibah was accorded a state funeral and laid to rest in the Muslim cemetery at Masjid Bahagian Kuching. In honour of her, a road at Kampung Masjid where she was born was named after her.

Although she had long returned home to be with her Creator, Ajibah left behind more than just memories to cherish. More importantly, she had bequeathed to the younger generation, especially those from the villages, the value and pride of struggle, the courage to rise and defeat social taboos, and the priceless power of knowledge that could help transform the community and steer the way to change and progress.

Hers was a vision of the new reality – a vision that arrived prematurely ahead of the time.

Yet, in anticipation of that, she had already planned to mould potential leaders and set the groundwork for them to grow and rise to become people who could lead and guide the community in politics and other spheres of activities.