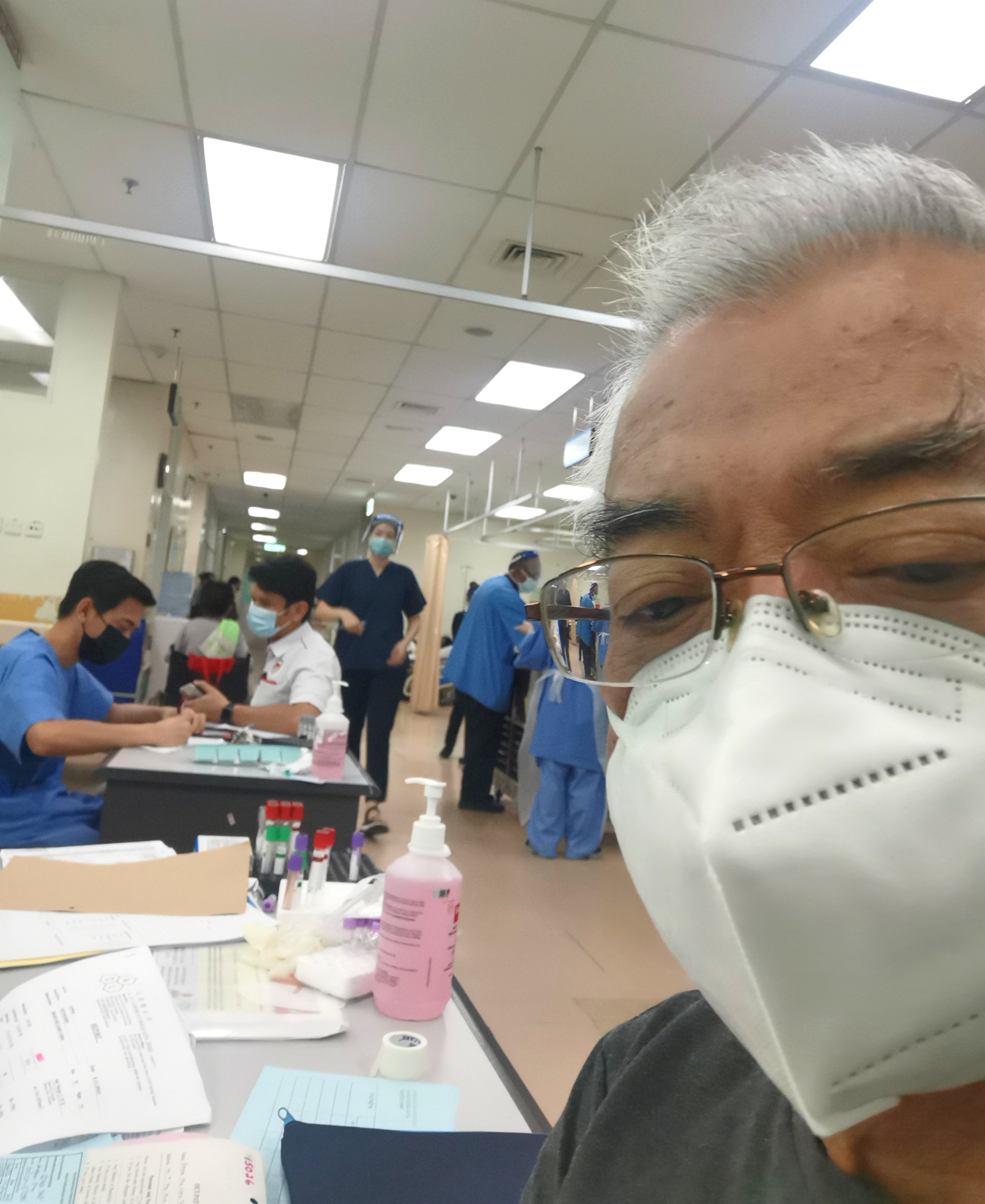

The writer among the Triage patients at the A&E — waiting.

AFTER having waited patiently for eight and a half hours at the A&E of Sarawak General Hospital (SGH) in Kuching on Thursday, I had sat down at my PC to write a scathing review of how our public health services needed to improve and what was wrong with it, and lots of other nasty remarks and suggestions for the better.

At my discharge 28 hours later, I had changed my mind – I was ready to write a more balanced report; indeed if you continue reading, you’d eventually get to my overall view of what’s going on there!

Last Thursday, at noon, I had decided to go to the A&E at the SGH to have an old internal injury seen to – it was life threatening as it involved quite an immense loss of blood situation. As I had a referral from an earlier cardiac consult at the Heart Centre in Kota Samarahan, I used the letter to register at the entrance – I was then told to go wait at the Triage for them to attend to me.

The wait at the Triage took almost 45 minutes, and I was told to wait at Door No 4 for my name to be called.

It was a busy afternoon, on Wednesday, Nov 10, 2021, and I could see that every single seat in the waiting room and along the corridors had been taken by waiting patients of all races, ages and at different stages of ailment.

I didn’t count the number of people, but could guesstimate probably around 30.

I waited very patiently. Others were being called in, I was wondering to myself: “This is supposed to be the A&E, which meant ‘Accidents and Emergency” – but these were not accident patients and I couldn’t figure out the emergency status from the external looks and appearances of those waiting.

I thought to myself that these patients were actually treating the A&E as if it were a general outpatient clinic, except that it might get them to see a doctor faster than the usual polyclinics!

I waited some more. Then by around 5pm, I had waited almost five hours and took a step to just go through Door No 4 to check if I were about to be seen to anytime soon. At a counter, I spoke to a male doctor, he was halfway through another patient; so I waited and spoke to the next one who came along, a lady doctor; and she asked my name and for me to follow her.

She brought me to a wall just next to the door No 4, which had many pigeon holes, like a post-office letter box, which were labelled with the colours green, yellow and red, apparently to separate the stages of emergencies.

She pulled my admission file from a green box.

I was sat down and asked the usual questions and my blood sample was taken and I was asked to wait some more.

She referred to the male doctor next to her on certain terms, medications and diagnosis and they had a quick chat. I was shown behind curtains to be physically examined. I was told to wait some more for her to refer to her senior.

After all this, I was informed that I was to be admitted for an endoscope to be done on me as well as more blood works to be carried out. I was asked to go to a small alcove of a waiting room facing the doctors/nurses centre desk to wait to be called once there was a bed available for me.

The waiting room measured about 12 feet by 20 feet and served as storage area for their cabinets and examination table for BP devices etc, and a cold freezer at the end of it. Lined against the walls were a five-seated plastic chair-deck a la airport style, and six fake-leather thin-cushioned lazy-chairs that had seen better days. These precious 11 chairs, I were to find out later, were to be my waiting room bed and resting place for the next ten hours! They were never unoccupied at any one time – patients would come and go, and everyone was either too sick to complain or too nice to make a fuss.

At around 4.15am the next day, I was told to move to a bed just behind and east to the nurses’ station. It was such a sweet relief after 16 hours!

By then, I hadn’t slept a wink.

Next morning, everything moved on like clockwork; I had a blood transfusion at 7.30am (I had lost too much blood by then and my haemoglobin level was way below the norms), I had my endoscope by 9.15am and everything was done and I only had to wait for the results and diagnosis.

Once I had entered Door No 4 the day before and seen what was going on inside – the other side of the picture, my views and opinions had changed 180 degrees!

But first, let me tell you a secret.

All of us get into some sort of medical distress, accidents or emergencies during our lifetime. We cannot time our emergency, nor can we determine when, how and how serious or the next time we have need of such emergency services.

In my case at the SGH A&E, it was sheer bad timing for myself. On that day, they had an extremely busy day, way above the average number of patients all decided to turn up at that particular time. As I checked out 28 hours later, the same A&E consulting rooms, the same Triage waiting corridors and the same waiting beds were quiet – there were more doctors waiting for patients and you could pick and choose which empty chair to sit and wait!

Such is the business of the A&E everywhere!

Such is life itself.

My experience of the A&E visit this time started as a total disaster and I was sharpening my wits to write a nasty review – I am going to end it with a roaring and stupendous hurray and a host of accolades for all the medical and administration staff, especially all those MOs, MAs, doctors, nurses and attendants who serve in the entire ETD department of the Emergency Ward; from what I can see, they all uniformly do stupendous, excellent work all around and are as dedicated, skilled and on their toes as anyone can expect of an A&E staff.

From their point of view, I am now able to see that they must first determine the stage of emergency at the Triage – green, yellow or red – and to treat patients accordingly.

Once inside Door No 4, they also need to quickly diagnose based on what they can physically diagnose and based on what they can obtain from the patients – bloodworks, scans, X-rays etc – and to prescribe the next course of action.

They must decide whether to admit or discharge with treatment/medication, which they do after having themselves obtained a second opinion from a peer or senior.

All these they must be able to do while on their feet, attending to a patient and doing everything virtually single-handed, and usually in a room full of other patients, doctors and nurses moving around at breakneck speed, doing their own things.

My original letter, published seven years ago, is still on the SGH Notice Board today.

Seven years ago, in 2014, I had written a very rousing open letter of thanks to the Director of the SGH, which was published on The Borneo Post. As I was on my way to the gent’s toilet at the A&E, along the corridor and on top of the ‘General Public Notice Board’, I had noticed that my letter was still posted there, at pride of position on the top right hand corner, atop some others from satisfied patients, mostly overseas. (But you need to stand on a chair to read it!)

I’ve always said this and I’ll say it again: as a society, as a community, we seldom show our appreciation for the good things that we encounter or the benefits that our state, our country, our government has given us – I’d like to once more say a big thank you to all our healthcare providers, all our public servants everywhere working in fields of service to the public.

Their personal efforts and hard work are very much appreciated, and for that, on behalf of the ‘silent majority’, we thank you sincerely from our hearts and we wish you all well – stay healthy and safe, and be assured that you are doing good work every single day.

Amen!