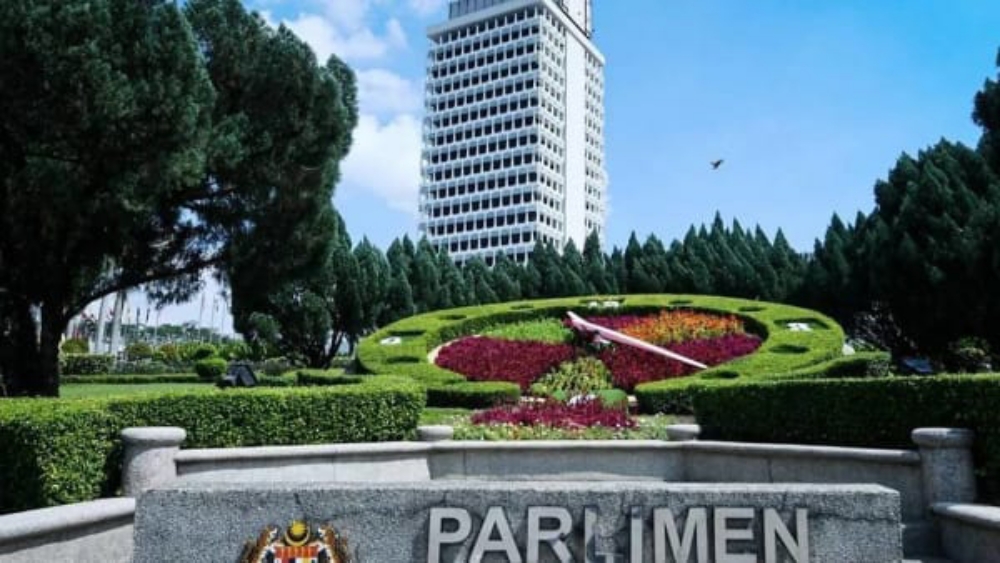

The Parliament building in Kuala Lumpur. The federal government should adopt UNDRIP and enshrine land rights of the indigenous peoples in legislation. — Bernama photo

TWO news items which I read from the media last week made me feel happy, as well as sad.

Happy, because His Holiness Pope Francis, during his visit to Canada last week, had joined a pilgrimage to a sacred lake for a symbolic healing of the ‘terrible effects of colonization, the indelible pain of so many families, grandparents and children’ (AFP, quoted by The Borneo Post of July 28, 2022).

Pope Francis’ apology relates to the Canadian government policy on the First Nations of Canada.

AFP reported that: “From the late 1800s to 1990s, Canada sent about 150,000 children into 139 residential schools run by the Church, where they were cut off from their families, language and culture. Many were physically and sexually abused, and thousands are believed to have died of disease, malnutrition or neglect. It is said that for some, the healing had already begun.”

Great is the power of apology and forgiveness.

Sad, because a thousand miles away from Canada, the Orang Asli of Malaysia, at the village of Bering in Kelantan, were complaining about disappearing herbs of medicinal value, blaming the loggers in their area for the disappearance.

The Temiar call this herb ‘Mangsian’ (Phyllantus reticulatus), a relief for tummy ache and fever. Soon they will have to get painkillers from the pharmacies in town.

In Malaysia, each state government has legislative jurisdiction over land matters. The Orang Asli in the peninsula enjoy the rights of usufructs only. Whatever land gazetted for their use is state land. My guess is that only a few of them have land under title.

Nothing has been heard about the work of the Cabinet Committee in providing legal aid to those indigenous peoples, including those in Sarawak and Sabah, involved in disputes over ownership or interest in land (see Annual Report 2016 of Human Rights Commission of Malaysia, Suhakam).

In politics, the Orang Asli have practically no clout, either in each state government or in the federal government. Their numbers are much smaller than those of the foreign workers, illegal immigrants and the refugees in Malaysia.

In terms of their share of economic development, they have not caught up with the rest of the population.

Passing interest only

Last month, I was following the proceedings of the Malaysian Parliament. During one sitting of the House, two members were talking about the conditions of the Orang Asli (Peninsular Malaysia) and Orang Asal (Sabah and Sarawak), each in turn stressing the need for the authorities to address their respective economic problems, except their land rights.

I was disappointed. It seems that either the MPs have no idea about the existence of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of the Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), or else they do not think it is worth their while to bring the matter to Parliament.

I’m not assuming that they are ignorant of the UN’s decision; not at all.

I’m appealing to anyone, from Sarawak or Sabah, who will offer himself or herself as a candidate in the next general election, to make the following United Nations (UN) Declaration as his or her election platform.

I have enclosed the relevant provisions of the Declaration here for ease of reference.

On Sept 12, 2007, the UN General Assembly during its 61st session, having discussed the Report of the Human Rights Council in respect of the rights of the indigenous peoples of its member countries, had adopted the Declaration.

Relevant to the Indigenous Peoples of Malaysia are the following provisions of the Declaration:

“Article 25: Indigenous peoples have the right to maintain and strengthen their distinctive spiritual relationship with their traditionally owned or otherwise occupied and used lands, territories, waters, and coastal seas, and other resources and to uphold their responsibilities to future generations in this regard.

“Article 26:

- Indigenous peoples have the right to the lands, territories and resources which they have traditionally owned, occupied or otherwise acquired.

- Indigenous peoples have the right to own, use, develop and control the lands, territories and resources that they possess by reason of traditional ownership or other traditional occupation or use, as well as those which they have otherwise acquired.

- States shall give legal recognition and protection to their lands, territories and resources. Such recognition shall be conducted with due respect to the customs, traditions and land tenure systems of the indigenous peoples concerned.

“Article 32:

- Indigenous peoples have the right to determine and develop priorities and strategies for the development or use of their lands or territories and other resources.

- States shall consult and cooperate in good faith with the indigenous people concerned through their own representative institutions in order to obtain their free and informed consent prior to the approval of any project affecting their lands or territories and other resources, particularly in connection with the development, utilisation or exploitation of mineral, water or other resources.

- States shall provide effective mechanism for just and fair redress for any such activities, and appropriate measures shall be taken to mitigate adverse environmental, economic, social, cultural or spiritual impact.”

The UNDRIP is now 15 years old. Some countries have implemented many of its provisions.

I read from the book ‘Conversations About Indigenous Rights’ – Massey University Press, 2018, in which editors Selwyn Katene and Rawiri Taonui confidently say: “In Aotearoa, New Zealand, the journey to full implementation is now under way…”

The ‘journey’ refers to recovery of Maori rights over land under the Treaty of Waitangi 1848.

Australia has a minister in charge of the affairs of the Aborigines and Torres Straits Islanders.

The ‘journey of recovery’ in Malaysia is slow. So far, the various efforts of the non-governmental organisations (NGOs) in getting heard have limited impact. They need the backing of the MPs from Sarawak or Sabah.

They also need the leadership of the Suhakam.

The synergised effort of these two could perhaps interest the federal government to look at UNDRIP more closely.

* Comments can reach the writer via [email protected].