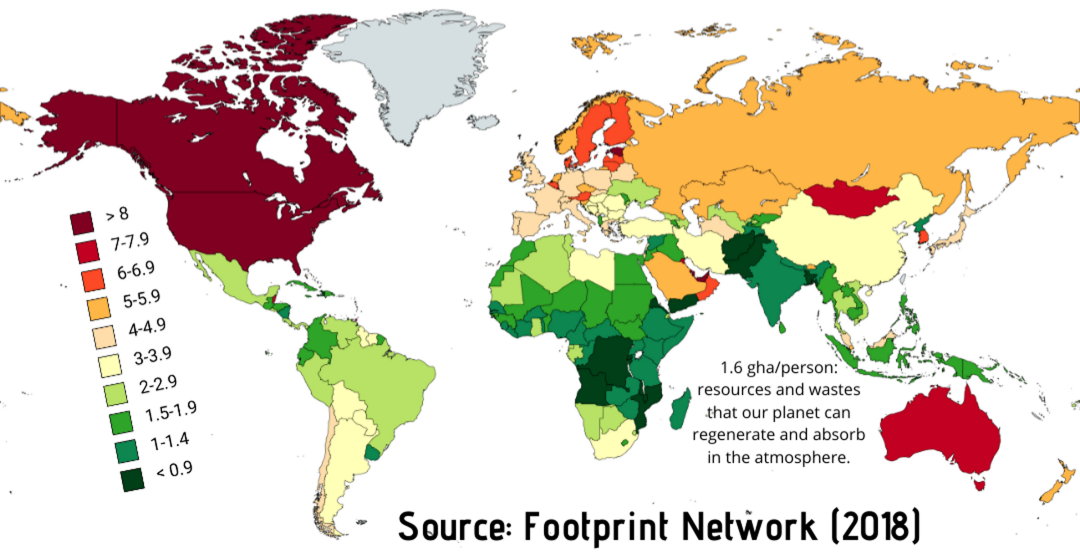

Ecological footprint per person is calculated by dividing a country’s ecological footprint by its population expressed in global hectare per person. — Map from Wikipedia/Ly.n0m

JUST spend a few moments pondering over the following:

- Wildlife numbers worldwide have fallen by 69 per cent on average from 1970-2018. This is the equivalent of losing all people in Europe, North and South America, Oceania, and China.

- Every year we lose approximately 10 million hectares of forests.

- Mangroves continue to be deforested by aquaculture, agriculture, and coastal development at a rate of 0.13 per cent per annum.

- Freshwater species of mammals, birds, amphibians, reptiles, and fish have declined by an average of 83 per cent since 1970.

- The six key threats to wildlife come from agriculture, hunting, logging, pollution, invasive species and climate change.

This staggering set of data has been taken from this report, published in October this year by the WWF in collaboration with ZSL (Zoological Society of London). It is a most readable and informative report and highlights that our destruction of wildlife is undermining our fight against climate change. Thoughtfully and eloquently written by over 70 global leaders from the fields of academia, NGOs, and ecology, it includes snapshots of ordinary people trying to make a difference to the environments and plights in which they find themselves.

This report is based on data gathered from 32,000 populations of 5,230 species across our planet and published in time for this December’s meeting at the Montreal United Nations Summit on A New Global Framework for Biodiversity. There, new targets need to be set to eliminate a 50 per cent decline in nature in the next decade for none of the targets set for 2020 have been met.

The red lights are flashing! In this week’s column, I shall attempt a summary of the 102-page report based on the premise that we all need to restore the health of the natural world.

Setting the scene

We are already experiencing the impacts of the decline of global nature and climate change. The latter is witnessed worldwide by the displacement and deaths of humans from increasingly frequent extreme weather events, increasing food security, depleted soils, a lack of access to fresh water, and the increase in the spread of zoonotic diseases.

These sadly fall disproportionately on the most marginalised and poorest people in our world. Attempting to address the complexity and diversity of the challenges we face, this report documents specific scenarios taken from Amazonia, Australia, Canada, Indonesia, Kenya, and Zambia.

The global emergency

Climate change and the loss of biodiversity are inextricably mixed. Over the last 50 years, biodiversity loss and the degradation of ecosystems have stemmed from increasing demands for energy, food, and materials occasioned by rapid economic growth, human population increases, and international trade. Today over one million plants and animals face extinction and we have already lost some 2.5 per cent species of mammals, birds, amphibians, reptiles, and fish. Our species are now losing their climatically determined habitats.

Since the industrial revolution (circa 1787), our planet has already warmed by 1.2 degrees Celsius. A rising average world temperature is most likely to become the dominant cause of biodiversity loss and the degradation of ecosystems in the next few decades, Already, 50 per cent of warm water corals have been lost and a global warming of 1.5 degrees Celsius will see the loss of between 70 and 90 per cent.

We need to conserve and restore biodiversity and limit human-induced climate change to reach Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), if everyone, no matter the size of their personal income, is to benefit.

Positive climate feedback has seen increases in wildfires, the desiccation of trees due to drought, insect outbreaks, peatlands drying up and tundra permafrost thawing, all releasing more carbon dioxide as dead plant materials are burned or decompose. Such traditional carbon sinks have now become new carbon releasers. Forests store more carbon than all the world’s exploitable oil, gas and coal and between 2001 and 2019 forests were found to absorb 18 per cent of all human carbon emissions.

Trees actually cool our planet by about 0.5 degrees Celsius and through evapotranspiration create rainfall providing water for the growth of food. Fragmentation of forests promotes the decline of wildlife habitats and the downward spiral of ecological dysfunctions, but this can be reversed by the creation of ecological corridors (as planned for the link between Mt Kinabalu and the Crocker Range National Parks in Sabah).

Speed and scale of change

A global map shows the hotspots of the threats to all terrestrial amphibians, birds and mammals and the threats they face. This is based on data from the IUCN Red List, and it appears that agriculture is the prevalent threat to amphibians and hunting and trapping are more likely to threaten birds and mammals. Southeast Asia is the region where species are likely to face threats at a significantly high level along with the dry forests of Western Madagascar, the Amazon Basin, the Northern Andes, the Himalayas and the tropical rainforests of West Africa. The hotspots in Europe are largely due to pollution.

The report continues with specific reference to the disappearance of our oceans’ sharks and rays with the larger bodied species showing a faster population decline because of their higher value for their volume of meat and fins. Because they reach sexual maturity late in life, they have less capacity to replace their numbers lost to fishing pressures. Today, we find that the world’s abundance of 18 out of 31 species of oceanic sharks and rays has declined by 71 per cent in the last 50 years.

Building a nature-positive society

The focus in this chapter highlights the UN General Assembly’s recognition that, “Everyone, everywhere, has the right to live in a clean, healthy and sustainable environment and for those in power realising that this not an option but an obligation.” It was the section entitled, ‘Humanity’s ecological footprint exceeds Earth’s biocapacity’ that caught my eye. Let me explain.

Most folk live within their means by balancing expenditure against income to create a state of dynamic equilibrium where output equals input. Earth’s biocapacity is the ability of its ecosystems to regenerate. However, people place great demands on this and both biocapacity and demand can be measured in terms of Ecological Footprints. It has been revealed that we overuse our planet by at least 75 per cent which is equivalent to living off 1.75 Earths!

World consumption figures, measured in terms of the ecological footprint per person, show that our planet’s biocapacity amounts to 1.6 hectares per person. If, for instance, a country’s ecological footprint is 6.4 global hectares per person, its occupant’s demands on nature for food, fibre, urban areas and carbon removal are four times more than what is available on our planet per person!

It is possible to reverse the trend of nature’s decline by diversifying in food production, income sources, robust markets and trade and by diversifying our diets. Last year almost 193 million in 53 countries experienced acute food shortages at crisis level. Almost 3.1 billion people cannot afford a healthy diet resulting in children suffering from stunted growth or wasting whilst the global obesity rates continue to grow. It seems that a transformative change is long overdue to place people and nature at its heart.

A very moving article is included in this report by Dr Eliud Kipchoge (double Olympic champion and world marathon record holder) who wisely stated, “We are the generation who inherited the world … and our great contribution will be anchored on sustainability. It is a race against time to save what is left of our home. Every minute counts like a marathon.”

Kipchoge planting a tree to honour Queen Elizabeth II on Blackheath Avenue in Greenwich Park – the start of the TCS London Marathon on Oct 4, 2022. — Photo via Facebook/Eliud Kipchoge

Through his own foundation, governmental and WWF-Kenya help, 225 hectares of forest land has been restored in just two years. A further 775 hectares at least are due for restoration by training local farmers in sustainable crop and animal farming in the Greening Kaptagat Landscape Restoration Programme. This cannot be achieved without indigenous people’s help and belief in their endeavours.

We can only attempt to recover what we have lost, through mismanagement and greed, with governmental help. As the world united to save mankind through investment in Covid-19 vaccines, we face a bigger problem in the form of climate change. Unfortunately, this cannot be treated by two jabs and booster doses. This project has a 30-year life from now and we all can learn from past mistakes and never repeat them. It is an urgent matter of now or never!

* I fully acknowledge the information I have taken from the WWF-ZSL Living Planet Report 2022 and suggest that readers refer to this report. It is only then that you will appreciate its breadth and depth.