The snailfish is the deepest living fish ever found at a depth of 8,336 metres. – Screengrab via YouTube/The University of Western Australia

AFTER a decade and a half of negotiations, finally in the late evening of Saturday, March 4, 2023, United Nations member states agreed to a text on the very first international treaty to protect the high seas, which cover half of our planet. Rena Lee, the Singapore chairperson of the conference, held at the UN Headquarters in New York, appropriately stated in her summing up speech, “The ship has reached the shore.” This pertinent announcement was greeted with loud and lengthy applause from all delegates.

This momentous treaty plans to cover 30 per cent of the world’s oceans by 2030. Our oceans create 50 per cent of the oxygen breathed by us and absorb 25 per cent of the carbon dioxide omitted by our activities on Earth. The carbon literally ‘sinks’ into the oceans and these ecosystems systems are vital to us all. Protecting areas in international waters will play a crucial role in building resilience to the impact of climate change.

How deep are the oceans?

Deep seas are defined as the ocean depths where sunlight begins to fade at a depth of 200 metres and are thus characterised by darkness, low temperatures, and high pressures. When I first studied A’ level Geography at school in the early 1960s, I was taught that the then deepest ocean trench was the Mariana Trench, off the coast of the Mariana Islands in the West Pacific Ocean, at 10,915 metres below the sea surface.

With refined echo-sounding techniques, its maximum depth recorded in the Challenger Deep (a section of the same trench) is now set at 10,920 metres. Put another way, if Mount Everest (at 8,410 metres) was submerged its peak would still be 2,000 metres below sea level. Today there are five ocean trenches deeper than 10,000 metres, two deeper than 9,000 metres, and four deeper than 8,000 metres.

Formation of ocean trenches

These are found at the convergence of plate boundaries where an oceanic plate meets an ocean plate or one oceanic plate meets another oceanic plate. The denser of the two plates plunges beneath the lighter one in what is known as the subduction zone (from the Latin meaning ‘leading under’). Usually, the denser plate is the oceanic one.

The Marian Trench is formed by the denser basaltic rocks of the Pacific Ocean plate plunging beneath the lighter, more recent rocks of the Mariana Ocean plate. Most ocean trenches are located around the Pacific Rim of Fire, but they are also found in the Eastern Indian Ocean, the Atlantic Ocean, in the Mediterranean Sea and off the West coast of South America.

Life in the ocean deep

It is often stated that more is known about life on the moon than is known about the deep oceans. These areas are certainly the least explored areas on Earth and our knowledge is certainly limited however with modern technology and the use of robotic submersibles we are getting there. This is no better illustrated than in a feature article in The Borneo Post (March 7, 2023) entitled ‘Drugs from the deep: Scientists explore ocean frontiers,’ which is a fascinating account based on the deep sea by researchers at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, based in San Diego, California.

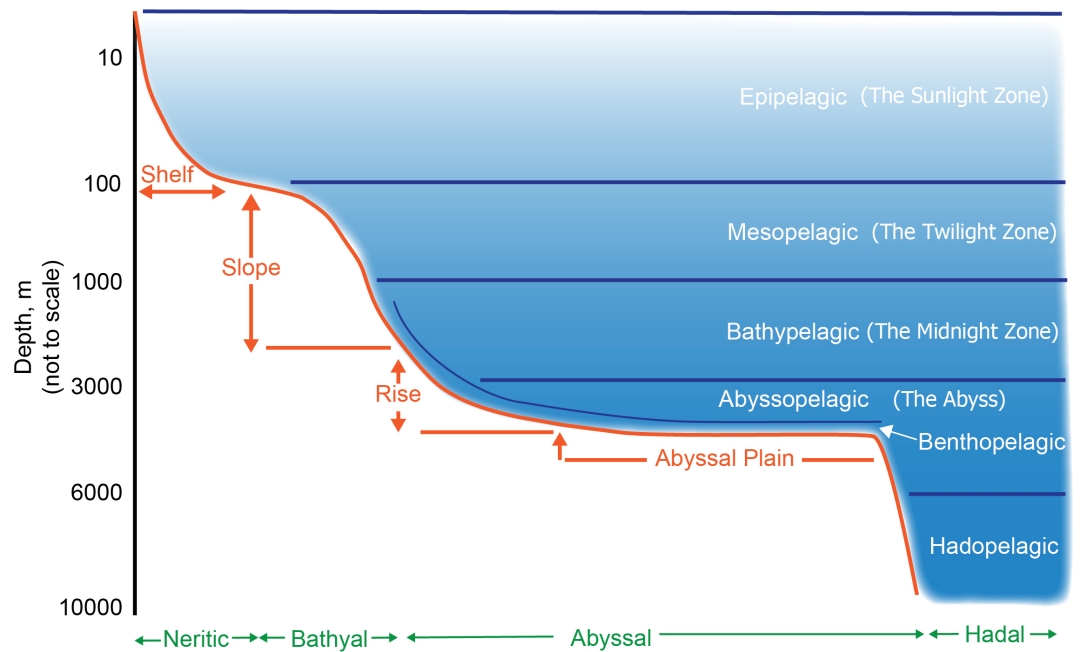

The ocean deep can be divided into four zones with depths recorded in metres below sea level: the Mesopelagic (twilight) zone from 200 to 1,000metres; the Bathypelagic (midnight) zone from 1,000 to 4,000 metres; the Abyssal zone from 4,000 to 6,000 metres; and, finally, the Hadal zone consisting of sea trenches from 6,000 to 11,000 metres. Each zone has a different mix of species adapted to its specific light level, pressure, and temperature.

The ocean deep can be divided into four main zones. – Diagram by Deepdisco/Wikimedia Commons

In the Mesopelagic zone fish, jellyfish, krill, and squid may be found and the most numerous family of fish is the bristlemouth. The Bathypelagic zone is an aphotic area with temperatures of 4 degrees Celsius. Creatures live with a minimal amount of food and have slow metabolisms and possess squishy bodies and slimy skins. Viperfish, angler fish, hagfish, gulper eels, vampire squids, and dumbo octopuses are resident there.

Many of these species are characterised by their grotesque shapes and very large recurved teeth and hinged jaws. Their source of energy is ‘marine snow’ which consists of dead plankton, diatoms, faecal matter, silt, soot, and inorganic matter. The ‘snow flakes’ collide and coagulate as they drift downwards, taking several weeks before reaching the ocean floor.

The Abyssal zone is characterised by hydrothermal vents caused by volcanic eruptions at the plate boundaries. These vents emit very hot water at 400 degrees Celsius, which is rich in minerals. This toxic soup of chemicals feeds bacteria which get their energy from the water through a process known as chemosynthesis. These bacteria, in turn, convert the chemicals into inorganic molecules which provide food for Giant tube worms found around the hydrothermal vents.

A crustacean living around these vents is the Yeti or hairy crab. Its Latin name is Hirsuita Kiwa named after the Polynesian goddess of shellfish. It is indeed hirsute, sporting fur-like hairs around its pincers. These hairs trap bacteria, which feed off the vents, and these bacteria provide the crab with its main food source. At this depth the pressure is 600 times that at sea level so creatures such as tripod fish, rattail, or grenadier fish, octopuses, and sea cucumbers are highly specialised.

The Yeti crab sports fur-like hairs around its pincers. – Photo by Andrew Thurber – Oregon State University/Wikimedia Commons

The Hadal zone revealed, only very recently in the Izu-Ogasawa Trench off Japan, the deepest living fish ever found at a depth of 8,336 metres – the snailfish. This pink skinned small fish is scale-less with large teeth and is mostly gelatinous to avoid using energy in a food deficient environment or in maintaining skin and scales. Using a remote-controlled camera able to withstand a pressure 800 times greater than that at the Earth’s surface, Professor Alan Jamieson of a Western Australian University managed to film this fish.

Many fish species have large tubular eyes for coping with scarce light at depth and others possess what is called bioluminescence. This is a chemical reaction that produces light energy within an organ’s body but, first of all, a fish must contain luciform, a molecule, which reacts with oxygen to produce light. Lantern fish use bioluminescence to lure their prey towards their mouths and for attracting mates. Deep sea worms living on the seabed produce a flash of this light to scare off impending predators.

Threats to deep ocean life

Global warming together with the increasing acidification of our oceans has led to the demise of many organisms and fish species. Deep sea trawling has destroyed, through its methodical raking of the seabed, a diversity of habitats and brought to fish markets alien looking fish which appear inedible!

Deep sea marine biology has also been affected by deep sea mining of ores, oil and gas has disturbed fish populations. Hopefully the new United Nations Treaty will go some way in the preservation of our open oceans. The French 19th century novelist Jules Verne in his famous book ‘20,000 Leagues Under the Sea’ certainly awoke the world to the wonders of the deep ocean and has continued to inspire 21st century research scientists.